Matthew J. Cressler, Ph.D., of Zócalo Public Square, wrote an article that appeared in the Smithsonian Magazine on June 7, 2018. In the article, he discussed the history of Black Catholics in America. An excerpt of that article is provided here.

Matthew J. Cressler, Ph.D., of Zócalo Public Square, wrote an article that appeared in the Smithsonian Magazine on June 7, 2018. In the article, he discussed the history of Black Catholics in America. An excerpt of that article is provided here.

The story of how Roman Catholics “became American” is very well-known. Beginning in the 19th century, Catholics were a feared and despised immigrant population that Protestants imagined to be inimical to, even incompatible with, everything America was meant to be. American mobs burned Catholic convents and churches. By the early 20th century, the antiCatholic Ku Klux Klan was running rampant.

But this changed after the Second World War. Military service, educational achievement, economic advancement, and suburbanization combined to make Catholics virtually (or, at the very least, statistically) indistinguishable from other Americans. Catholics became “mainstream.” The culmination of Catholic Americanization arrived, symbolically, with the election of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy in 1960. By 2015, when Pope Francis was invited to speak before Congress, one-third of its members were Catholic.

There is a problem with this popular story, however, because it applies only to the children and grandchildren of European Catholic immigrants. A second story involves their black coreligionists, who not only took a different path but also challenged this popular narrative. The true story of Catholics “becoming American” must include the black Catholics who launched a movement for acceptance within their own Church, and within the country. In the process, they transformed what it meant to be both black and Catholic while creating a substantial and sustained critique of the U.S. Catholic Church’s complicity in white supremacy.

On April 16, 1968, less than two weeks after the assassinated of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Father Herman Porter, a black priest from Rockford, Illinois, convened the first meeting of the Black Catholic Clergy Caucus in Detroit. Fifty-eight black priests gathered with at least one Brother and woman religious (or “Sister”) to draft the statement that inaugurated a national Black Catholic Movement. Its provocative opening words were: “The Catholic Church in the United States, primarily a white racist institution, has addressed itself primarily to white society and is definitely a part of that society.”

The priests accused the U.S. Church of complicity with white supremacy; they demanded that black people be given control of the Catholic institutions in black communities; and, perhaps most surprising of all, they insisted that “the same principles on which we justify legitimate self-defense and just warfare must be applied to violence when it represents black response to white violence.”

This was the time, they said, for black Catholics to lead the Catholic Church in the black community. For “unless the Church, by an immediate, effective and total reversing of its present practices, rejects and denounces all forms of racism within its ranks and institutions and in the society of which she is a part, she will become unacceptable in the black community.”

Later that same year, Sister Martin de Porres Grey organized the National Black Sisters’ Conference, challenging black sisters to involve themselves in the liberation of black people. The sisters’ statement was no less radical than that of the priests. They denounced the “racism found in our society and within our Church,” declaring it “to be categorically evil and inimical to the freedom of all men everywhere, and particularly destructive of Black people in America.” The sisters pledged themselves “to work unceasingly for the liberation of black people” by promoting “a positive self-image among [black folk]” and stimulating “community action aimed at the achievement of social, political, and economic black power.”

The National Convention of Black Lay Catholics, organized in 1969, soon followed suit and, by 1970, these allied organizations had exerted enough pressure on the national body of U.S. Catholic bishops to win official approval for a National Office for Black Catholics based in Washington, D.C.

For more information and to read the full article, please go here.

For more on Dr. Cressler’s work about Black Catholics, go here.

![]()

March 11 @ 1:30pm at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception

March 11 @ 1:30pm at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception LETTER OF THE HOLY FATHER, FRANCIS, TO THE BISHOPS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

LETTER OF THE HOLY FATHER, FRANCIS, TO THE BISHOPS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Edited reflection by Francis DeBernardo, Executive Director, New Ways Ministry

Edited reflection by Francis DeBernardo, Executive Director, New Ways Ministry As I begin my term as President of Dignity Washington, I have thought a lot about what I hope to accomplish in the next year. After all, a year (11 months really) is not a very long time. Nevertheless, there are a few activities where I would like to focus my energy and attention.

As I begin my term as President of Dignity Washington, I have thought a lot about what I hope to accomplish in the next year. After all, a year (11 months really) is not a very long time. Nevertheless, there are a few activities where I would like to focus my energy and attention. Thank you for trusting me with the responsibilities of chairing the Liturgy Committee. I have been asked to introduce myself and explain my vision for the committee.

Thank you for trusting me with the responsibilities of chairing the Liturgy Committee. I have been asked to introduce myself and explain my vision for the committee. It is with great sadness that the president, officers, and Board of Directors of Dignity Washington announce the death of long-term member and former DW President (1990–1993), Bernie Delia, on Friday, June 21st, at his home at age 68.

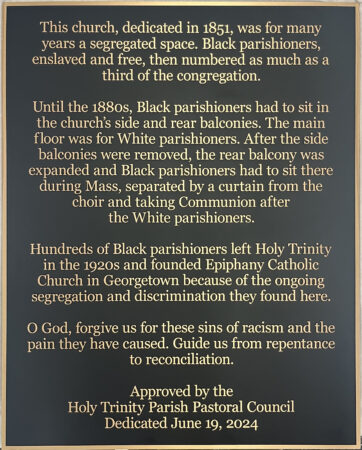

It is with great sadness that the president, officers, and Board of Directors of Dignity Washington announce the death of long-term member and former DW President (1990–1993), Bernie Delia, on Friday, June 21st, at his home at age 68. It’s a LATE notice, but we wanted to ensure that everyone knew about this opportunity at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown.

It’s a LATE notice, but we wanted to ensure that everyone knew about this opportunity at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown. Dignity Washington clearly demonstrated our pride during the main Capitol Pride 2024 events. About 25 members attended the Night Out with the Nationals last Thursday and while the game didn’t produce a curly “W,” it was a lovely evening to watch the game and share conversations among friends.

Dignity Washington clearly demonstrated our pride during the main Capitol Pride 2024 events. About 25 members attended the Night Out with the Nationals last Thursday and while the game didn’t produce a curly “W,” it was a lovely evening to watch the game and share conversations among friends.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15786728/facebook-video.0.1462601647.jpg)